Let’s face facts: The Make in India initiative did not really produce the dividends it was expected to. One can say that the Atma Nirbhar Bharat programme launched in mid-May is an improved version of the earlier scheme. Analysts are optimistic about the results provided the implementation is done in a proper manner. We will weigh the pros and cons in this article.

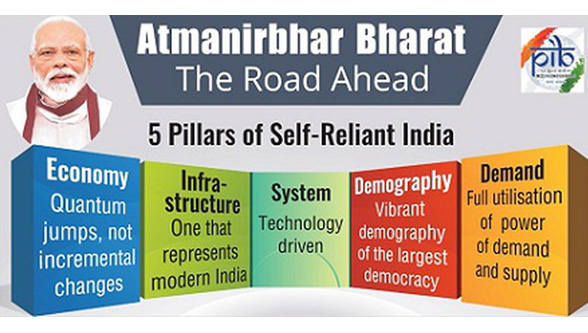

In view of the Covid-19 pandemic, Atma Nirbhar Bharat Abhiyan, announced by PM Narendra Modi, aims to propel the country on the path of self-sustenance and insulate India from any future global economic downturn.

The Prime Minister unveiled the Campaign for Self-Reliant India in mid-May, some commentators focused on its title rather than its substance. Its name – Atma Nirbhar Bharat Abhiyan in Hindi – indeed makes one think that the initiative is permeated with the idea of self-reliance.

Analysts are hopeful that Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s Atma Nirbhar Bharat programme will be a bigger success than ‘Make in India’ to boost India’s manufacturing.

This time around, with ‘Atma Nirbhar’ (self-reliance), there is a targeted focus on specific sectors — defence, pharmaceuticals, and electronics sectors are most likely to reap the benefits.

Six years after ‘Make in India’, analysts are hoping that the Atma Nirbhar Bharat programme will have more material impact on the country’s manufacturing sector. With the ‘Make in India’ programme in 2014, the Narendra Modi government was pushing for a one-size-fits-all solution across 25 sectors.

“None of the key parameters suggest any material improvement in the performance of the manufacturing sector over the last six years,” said a report by Citi Research highlighting the inefficiency of Make-in-India. The share of value-added by the manufacturing sector to the country’s overall production has remained stagnant between 17 per cent and 18 per cent over the last decade.

Focusing on specific sectors and pushing for local products to replace imports is the government’s new strategy.

Electronics, pharmaceuticals and labour-intensive industries may be the biggest beneficiaries of Atma Nirbhar Bharat.

With Atma Nirbhar Bharat, analysts see the policy focus shifting from exports and attracting shifts of supply chains to providing fiscal incentives and putting in import restrictions instead. Most companies are anyway going to adopt a ‘China plus 1’ strategy rather than entirely move out of China.

Exports will remain the key focus, as in any developing economy. However, the fundamental difference between ‘Make in India’ and Atma Nirbhar is the realisation that India can’t control what the world will buy and therefore, it should focus on its strengths instead of playing in areas where the global competition is intense.

Before forcing the world to buy from India, the Modi government had to ensure the people of the country were willing to buy local brands. Cheaper imports, everything from mobile phones to textiles to steel – particularly from China – had to be fended off.

The border tensions in Ladakh gave India the political impetus it needed to put its plans in place, starting with putting a cap on Chinese investment into India.

Let’s take pharmaceuticals, for instance. “Out of India’s total bulk drug imports are 63 per cent of total pharma imports and for some medical equipment the import dependency could be as high as 86 per cent,” said the Citi Research report. The government has marked the pharmaceutical sector among the 10 ‘champion’ sectors and as a part of this, India is looking for international companies that would like to move their manufacturing base to the country.

Exports still remain an integral part of Atma Nirbhar Bharat. However, rising global protectionism, reneging on bilateral foreign trade agreements, and the expiry of India’s most prominent export incentive scheme — Merchandise Export Incentive Scheme (MEIS) — indicate that the push on exports is weakening.

Margins is where value addition kicks in. It’s not enough for exports to grow, they also need to bring more value in order to have a beneficial effect on the economy. Otherwise, some sectors may grow at scale but they won’t necessarily add to the profit bottom line.

The foundation for this was laid out ahead of the budget earlier this year, in India’s annual Economic Survey. The Survey went on to say that while the short- to medium-term objective is the large-scale expansion of assembly activities by making use of imported parts and components, giving a boost to domestic manufacturing of parts and components (upgrading within global value chains) should be the long-term objective.

So far, pharmaceuticals, defence manufacturing and electronics have been given incentives to make more value-added products in India. Going forward, labour-intensive sectors like leather, textiles and food processing are likely to see similar thrust, according to Citi Research.

One of the few success stories of Indian manufacturing is the electronics goods production. During the last couple of years, exports have doubled to $11.8 billion in 2020 from $6.4 billion in 2018. However, though the volume of production may have increased, concerns were raised over value addition.

“A domestic electronics component manufacturing ecosystem had to be developed to reduce dependence on imports and fiscal incentives are planned to develop that ecosystem,” said Citi’s report.

The idea has definitely improved from Make in India to Atma Nirbhar, whether the results will be better is something to be seen in a few years from now.

Article by Arijit Nag

Arijit Nag is a freelance journalist who writes on various aspects of the economy and current affairs.

Read more article of Arijit Nag