John Young, APAC director at EU Automation, examines the problem of industrial obsolescence and the trends that guarantee its increasing prominence.

In 1924 a global organization hatched a plan to limit the lifespan of light bulbs from 2,500 hours to 1,000 hours. The Phoebus Cartel is a proven conspiracy and probably the best-known example of planned obsolescence. However, modern examples of obsolescence are rarely driven by conspiratorial activities.

We are all familiar with the problem of obsolescence in our day-to-day lives. I want to buy a new set of headphones, but I am worried that a year from now my newly upgraded mobile phone might come without a headphone jack as wireless Bluetooth headphones become more widespread.

This dilemma is greater in industry. Suppose a part breaks down and you need to source a replacement. However, the part itself is obsolete. If you have a reliable parts supplier you might be back up and running quickly. Without that service, downtime is costing you as you confront the dilemma. Does this mean you have to fork out for an entire system upgrade? Whatever the answer, it is precisely this sort of problem that will face manufacturers with growing regularity in the years ahead. Here’s why…

The cost of progress

Technological obsolescence refers to when a product or service becomes obsolete because it is no longer wanted or needed. A product may still work perfectly well but there are newer, more sophisticated versions available. This obsolescence is therefore a natural and inevitable consequence of technological advancement. The increasing speed of this advancement is one factor that will drive increasing obsolescence in industry in the coming years.

Reliance on IT

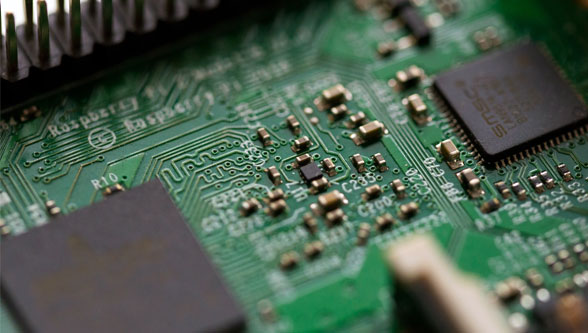

An equally important but perhaps less understood factor is the impact of the convergence of manufacturing with IT and digital technologies. If you want to avoid the costs of obsolescence, can’t you just pick products and systems with longer lifespans? The convergence of IT and industry means that current and future generations of manufacturers simply won’t have this option to the same degree that their predecessors did.

For example, if you go back thirty or forty years, control system vendors typically enjoyed total control over their product cycles. Subsequently, the smarter vendors began introducing components and sub-systems from the world of IT. The benefits of this were improved development costs but it also exposed industry to reliance on much shorter product and component lifespans.

Exposure to consumer markets

This overlaps with yet another unappreciated factor that is driving obsolescence. The increasing reliance on IT and electronics exposes industry to patterns and dynamics that are driven by consumer markets, not the needs of industrial manufacturers.

Semiconductors, the key building block in modern computers and electronics, are a great example of this issue. Today, the manufacture of these chips is driven by the needs of a consumer market and product lifespans can be as short as two years. In contrast, in the 1970s and 1980s, many device types were in production for 25 or more years.

Planned obsolescence, such as the scheming of the Phoebus Cartel, might impact manufacturers indirectly via this route. However, the more important point is that the impact of IT and the growth of the consumer electronics market have changed the game for industrial manufacturers.

Obsolescence, ironically, is not going anywhere. Getting to grips with this reality requires understanding the long-term trends that increase its prevalence. These trends do not require any encouragement from cartels and conspirators. As I have suggested, increasing obsolescence in industry will be driven by many things but accelerating technological advancement, growing reliance on IT and trends in the consumer electronics market are the key.